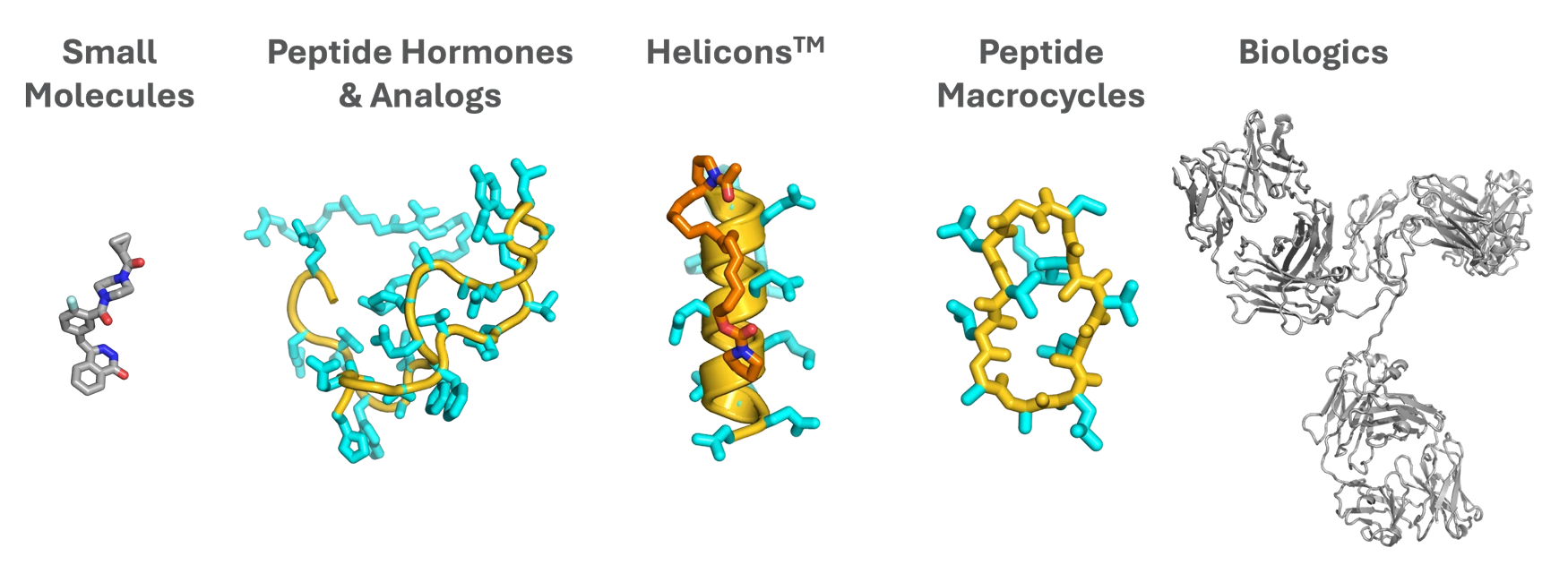

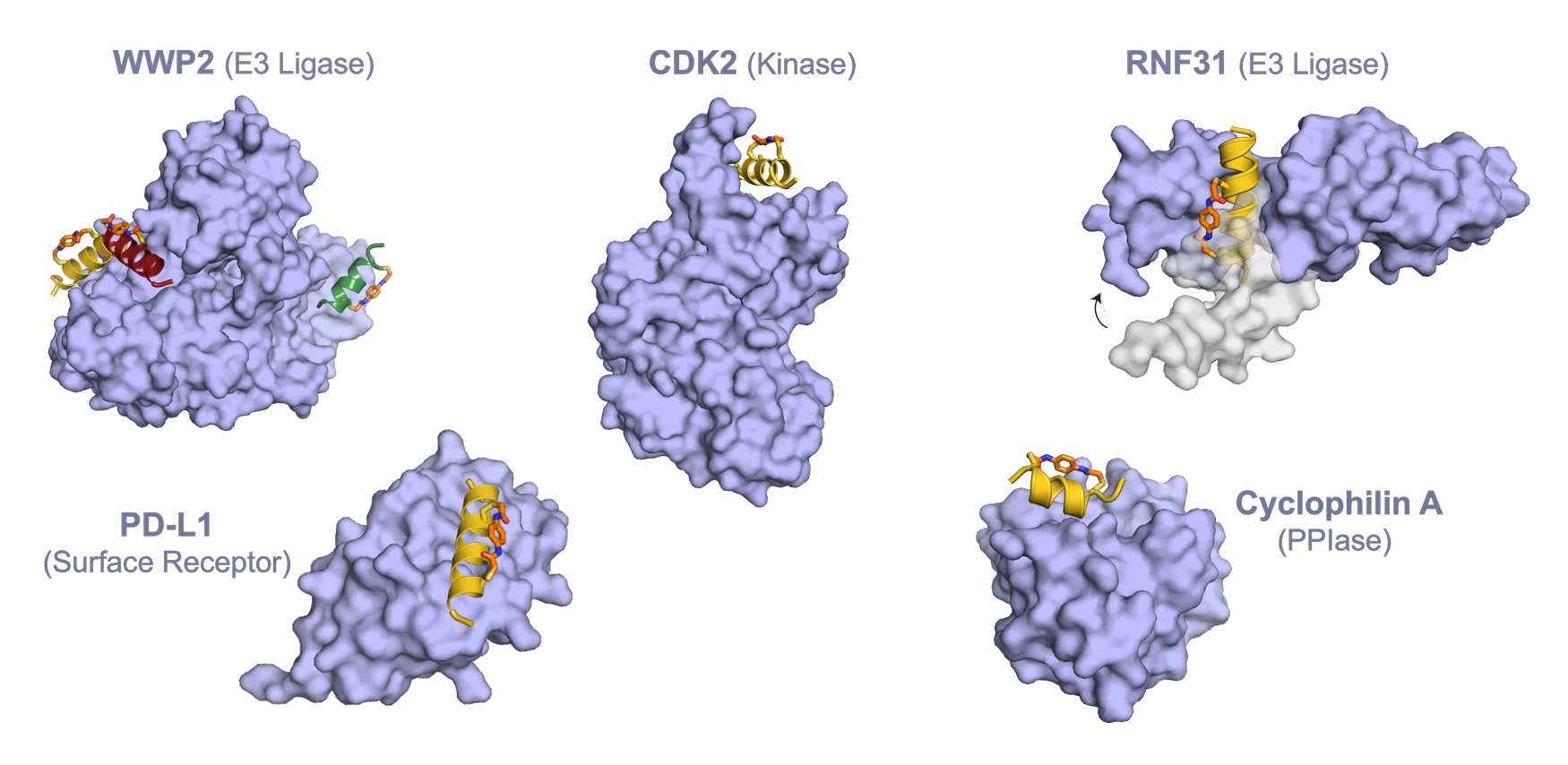

Before we dive into stories of our day-to-day research, we think it’s worth sharing why we have such deep conviction that constrained alpha-helical (Helicon) peptides will be unique and impactful medicines. There is a dizzying array of modalities being pursued by our industry today, including a variety of peptide-based approaches. Most teams attempting to access intracellular targets with peptides are focused on cyclic, rather than helical, structures. The appeal of cyclic structures is understandable, and we believe and hope that they have the potential to lead to important therapies. But at Parabilis, we have shown that helical structures have unique properties that give them the potential to enter cells efficiently and engage difficult protein targets that require significant size, charge, or polarity for selective and potent binding.

So why Helicons?

Helicons are special because they follow different rules than both small molecules and non-helical peptides, especially (though not only) when it comes to cell penetration. Helicons can robustly enter cells bearing impressive collections of functional groups, such as fifteen amide bonds plus three negative charges, that would ordinarily have no chance of crossing a membrane as part of another modality.

Helicons combine the targeting power of antibodies with the cell penetration of small molecules

This unique ability can be explained, at least in part, by physical principles and by observations from nature. The alpha-helical fold is formed by a series of repeating intramolecular hydrogen bonds between a backbone carbonyl and the amide proton of the amino acid four residues ahead in the polypeptide chain. Helices thus intrinsically “cloak” a significant fraction of the polar groups that a peptide will contain from interaction with the surrounding solvent or membrane. Consequently, the polarity (or lack thereof) of a helical peptide is largely determined by the composition of the amino acid sidechains, which can allow them to exist in lipophilic membranes if they are sufficiently hydrophobic. Helices thus possess an inherent structural feature that suggests a privileged ability among other protein folds to achieve the properties required to exist in lipid membranes, which is essential for a molecule to enter cells “gently,” without disrupting membrane function or integrity.

Inspiration from Nature

The helical fold intrinsically cloaks amide protons and carbonyls throughout the polypeptide chain

Turning to nature, we can find abundant evidence that this is the case: nearly all single-spanning transmembrane protein domains, across every domain of life, are composed of alpha helices. Evolution has been running experiments on protein folding and function for billions of years, so to see such a strong vote in favor of the alpha helix is striking.

And nature has also chosen the helix for a second, equally relevant use: its ability to strongly and selectively engage protein surfaces. Helices are one of the most common recognition elements found in natural protein-protein interactions, both as isolated helical stretches and as part of larger folds or bundles. The Helicon modality was born in the late 1990s when Greg Verdine and members of his lab connected these observations – the fact that nature has repeatedly reached for the alpha helix both to embed in membranes and to bind protein surfaces – with the emerging realization in the pharmaceutical industry that small-molecule drugs were incapable of engaging a large and highly relevant subset of therapeutic protein targets within cells.

Helical peptides can bind a wide, diverse range of protein surfaces

Other peptide modalities also seek to cloak or manage backbone amides in various ways. For example, those drawing inspiration from natural products such as cyclosporine may employ alkylation or transannular hydrogen bonding. But the alpha helix has amide cloaking automatically built into a structure with broad targeting power, meaning the conformations enabling cell penetration and binding can be the same. This eliminates the challenging optimization typically required for non-helical macrocyclic peptides to balance permeability with binding.

Importantly, Helicons do not require cationic charges that interact with or disrupt membrane structure in order to enter cells. There has been a large volume of work reported in the field of “cell penetrating peptides” (CPPs), most of which contain multiple cationic residues, sometimes in combination with lipophilic moieties. While such molecules can give the appearance of in vitro and occasionally even in vivo biological activity, they are generally not viable as therapeutics due to unfavorable drug-like properties, particularly their safety profiles.

Helicons, in contrast, do not require cationic charge to enter cells; Parabilis has discovered many in vivo active chemical series (including our clinically validated beta-catenin:TCF inhibitor FOG-001) with zero positively charged residues. Helicons are not conjugated to lipid tails, or any other moiety intended to drive cell penetration. They are intrinsically cell penetrant, enabling delivery to animals and patients without the need for unconventional formulations or enabling technologies.

Open questions

This post has largely focused on the unique alignment of amide cloaking ability with targeting power as a foundational rationale for our belief in Helicons as a transformational drug modality. But the amide cloaking of alpha helices, and the precedent of natural transmembrane domains and protein-protein interactions, do not explain every attractive feature of this modality. For example, we have shown that Helicons are able to safely enter cells bearing arrays of sidechains that themselves can contain substantial charge and polarity, which appears unique to Helicons and allows them to engage proteins that other types of molecules cannot.

We have also found that Helicons can possess extremely long half-lives in vivo, appear to evade immune recognition, can include functional groups that would undergo problematic metabolism if incorporated into a small molecule, and seem highly amenable to heterobifunctionalization. All of these properties remain the subject of active investigation in our labs, and in future posts, we’ll dive further into our hypotheses and observations on these topics as we continue to explore a modality that continues to inspire and amaze us.

Authored by John McGee, Platform Technology team member